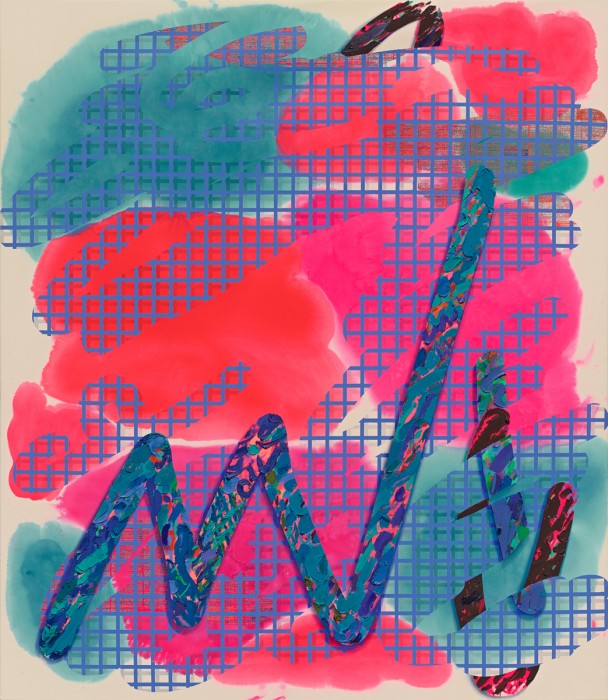

Laura Owens, Untitled, 2013, Acrylic, Flashe and oil on canvas, 137.5 x 120"

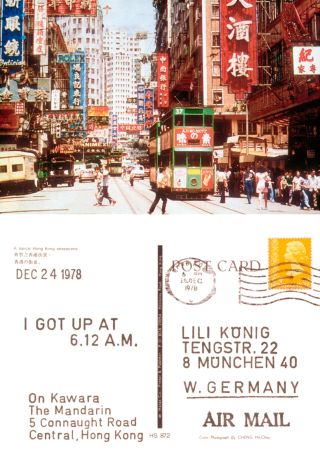

On Kawara, DEC 24 1978, from the series "I Got Up," 1978

Courtesy Lili König Collection

Justin Beal, Murmansk, 2013

Tauba Auerbach, The New Ambidextrous Universe IV, 2014

Plywood and aluminum

96 x 48 x 1.5 inches

243.84 x 121.92 x 2.8 cm, reconfigured

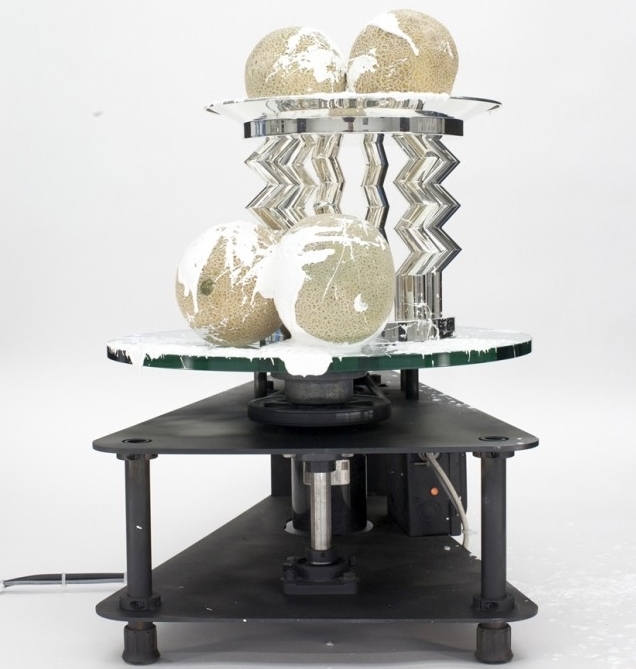

Tauba Auerbach, Gnomon/Wave Fulgurite I.II, 2013

Sand, Garnet, Shell, Glass and Resin / Glass and spray lacquered wooden plinth

26 x 11 x 2 in.

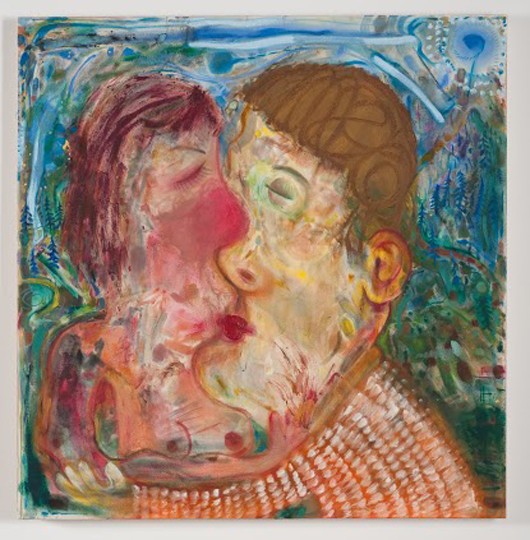

Nicole Eisenman, Springtime Kiss, 2011, 40 x 41.5"

Kathryn Andrews, Serial Killer, 2012.

Image courtesy the artist and Clifton Benevento. Photo: Aaron Igler + Matthew Suib/Greenhouse Media

Kelly Nipper, Sapphire (detail), 2008

A Performa Commission with the Savannah College of Art and Design

Haegue Yang, Female Native – Saturation out of season, 2010

Courtesy of Kukje Gallery, Seoul

Photography by Nick Ash

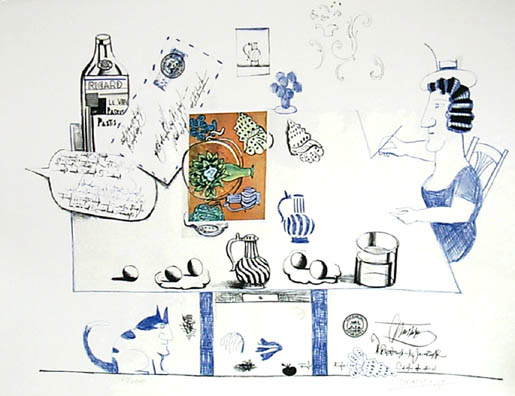

Saul Steinberg, Matisse Postcard, 1970

(From "Six Drawing Tables")

Lithograph, collage on paper; Ed. of 100

22" x 30"

Courtesy Adam Baumgold Gallery